I wrote recently about the history of the belt in Scottish schools, focusing on the ways in which commercial interests helped to sustain this brutal practice. I enjoyed hearing from readers who found my observations discomforting. One primary teacher commented that he “actually had to sit down” upon reading that a miniature strap had been available to order, “intended for use on very small children or as a toy, at a cost of only 33p”.

My research for that piece left me wondering about the history of the cane in English and Welsh schools. Who manufactured those devices? How much did they cost? How were they marketed to schools? And what was the impact on that income stream once corporal punishment was banned in schools? These are fascinating questions because they have been largely overlooked. The passage of time seems to have robbed us of an awareness that canes were commercial products, purchased by schools as a form of equipment, in much the same spirit as sporting or music equipment. The purpose of that ‘punishment equipment’ was dark, of course, in that its intention was to cause children pain. This purpose was one that manufacturers endorsed. Indeed, they were making money from it.

This history deserves to be better understood, not just for its own sake, but because it illuminates the way in which denial operates. That is the central aim of this series – to explore the role that denial plays in obstructing change that improves children’s lives. When we look back to practices that have now been discarded, we increase the possibility of seeing where we might be living in denial today. Those discoveries are always uncomfortable. They reveal things about ourselves and our culture that we might prefer to ignore. That’s why I call this stance ‘Fierce Curiosity’. When you have to look at things that are uncomfortable, when ordinary levels of curiosity won’t do, when it takes courage to look – that’s when you need Fierce Curiosity.

Debate continues today about how to manage the behaviour of children and young people in schools. Should isolation booths and silent corridors be adopted? Or should nurture practices and trauma-informed policies be put in place? Tension rises sharply between advocates of these two camps. Perhaps examining previous debates can yield insights that will help in making sense of these modern ones?

Tracing commercial aspects of school corporal punishment in the 1970s and 1980s turns out to be useful in this regard.1

The design and use of canes

Before we turn our attention to suppliers, let me describe the design and use of canes. This ensures that everyone is aware of the ways in which this ‘equipment’ was applied to the bodies of children and young people.

Canes came in two basic styles. The first was the ‘swishy cane’, like the ones that feature in the schoolboy stories of Billy Bunter. This style was thin and bendy, intended to leave a burning sting. It was typically a straight stick with a wrapped handle added to one end, making it easier for the teacher to hang on to. The second style was stiffer and thicker, usually fashioned into the shepherd’s crook handle that has come to be thought of as a ‘Headmaster’s cane’. This style had a wider diameter, about the width of a thumb, which landed on a child’s lower body with a kind of thud. It left a deeper reverberating pain, rather than the burning sensation of the swishy cane.

Canes were made of rattan and cut to various lengths. The most common were 24, 30, and 36 inches, with shorter canes being intended for use with younger children. Longer canes resulted in more pain. There is distaste, from our perspective today, in the idea that adults would strategically plan to increase levels of pain as children mature. This was an old idea, though, transferred from the days when the Royal Navy employed punishments such as birching and flogging. Once the notion of developmental pain thresholds had become embedded within the education system, it would function automatically. It would become normative. Maturational alterations were needed for other forms of children’s equipment, such as football boots. Why wouldn’t punishment canes alter as children got older?

How were canes used? Strokes, or ‘cuts’, were delivered to a child’s bottom, legs or hands. They typically numbered between one and six, although there are stories of twelve or more being delivered for very serious matters such as theft or pulling a knife or openly homosexual behaviour. Strokes on the hand were usually delivered on the upturned palm, while those to the lower part of a child’s body required them to ‘take the position’ of bending over a desk or stool or, alternatively, leaning forward to touch their toes. Generally, pupils were allowed to remain clothed, but some schools, for some misdemeanours, instructed them to lower their trousers or raise their skirt. Sometimes they were even required to lower their underpants, resulting in a caning on the naked bottom. Most teachers delivered strokes while standing still, although there are plenty of stories of teachers adding force by running up to the child’s body, mimicking the swing used in a game of cricket. Caning was intended to leave red marks, welts and even bruises. Severe canings might draw blood. The advice to staff was that there was no sense using the cane unless they made it hurt.

By the 1970s, schools were often issued with official guidance about how caning should be carried out. The aim was to standardise practise, even though the specifics differed across regions. This codification addressed issues such as the maximum number of strokes that could be delivered; was it three or six or twelve? Should the caning of girls differ from that of caning of boys? At what age should children be graduated from the smaller ‘prep cane’ to the more vicious ’senior cane’? Was it only headmasters who were allowed to administer canings or were other members of staff permitted to do so? Was it necessary to have a witness present? Should a caning be delivered soon after the offending act, or should there be a cooling off period? Should pupils be required to say ‘thank you’ afterward? Sometimes guidance didn’t address caning at all. It simply stated what teachers were not allowed to do, such as slap a pupil’s head or box their ears. And of course, written guidance from local authorities applied only to state schools. In private schools, there was no requirement for such standardisation. Each institution made its own rules.

These forthright descriptions make clear the cruelty of these practices. What is obvious to us now would have been harder to see at the time. The normalisation of the practices blinded adults to the brutality. Where they could see it, that brutality was often esteemed. The pain, humiliation and fear were believed to improve a child’s behaviour and to strengthen their character. When members of STOPP (the Society for Teachers Opposed to Physical Punishment) began to campaign for the abolition of corporal punishment in 1968, they encountered intense resistance from many teachers, unions and parents. It would be nearly 20 years before the ban they sought was achieved. That came into force in 1986 in state schools and in 1998 in private schools.2

So who were the companies that manufactured and sold punishment canes? How did schools submit their requests? Do we know much income was derived from the sale of canes? And why does this line of questioning seem odd? Why have the commercial elements of corporal punishment gone unnoticed amidst the many stories that survive of this practice?

Coopers of England

Coopers of England was a stalwart supplier of punishment canes, even though that wasn’t their primary activity. Fundamentally, they were a gentleman’s accessories outfitter, with a reputation for tradition and prestige. First established in 1850, on a country estate in Surrey emblematic of the Victorian age, Coopers came, over time, to be regarded as Britain’s oldest and biggest walking stick maker. An article published in 1994 in The Observer describes their beautiful, high-quality products, fashioned from any type of wood (or other sturdy plant, like rattan) into any style of cane one wished. A single sentence in the article captures the unexpected intersection of privilege and punishment, when it describes Coopers in this way:

“Purveyor of walking sticks and umbrellas to the gentry, and of canes to schools all over Britain, for the last 150 years”.

That unsettling sentence deserves to be read slowly: “Purveyor of…canes to schools all over Britain.” And then there’s the even more startling sentence at the beginning of the piece: “The shop is a sadistic headmaster’s dream.”

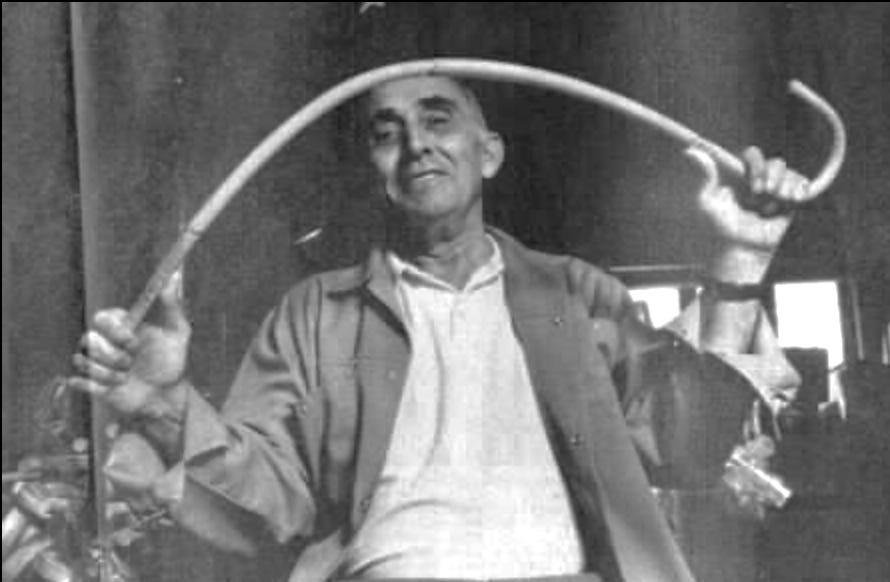

The Observer article interviews Mr Stan Thorne, a Cooper employee for 52 years. He remarks that during the 1950s and 1960s, the company’s annual sales to schools were in the region of 6000 canes. “Eager headteachers were asking for dozens of canes at a time. Some of the Heads were very enthusiastic. They went through canes like nobody’s business.” The article includes his photograph, accompanied by a caption that reads: “Stick maker Stan Thorne, who disapproves of corporal punishment, demonstrates the swish in a Coopers' cane”. Whether or not that disapproval was true, the photograph itself is valuable, because it brings this slice of British history to life in a way that none of the written descriptions can quite achieve on their own.

How frequently were Coopers’ canes employed in acts of beating children? That is hard to determine. In my earlier piece on the Scottish tawse, I estimated that the leather products manufactured by the leading company John Dick & Sons were involved in at least 10 million acts of violence, during the 40 years between 1945 and 1985. That estimate was based on a small set of records, given that punishment records were not generally kept in Scottish schools. The converse applied in English and Welsh schools. Headteachers were expected to keep records of canings, often accompanied by signatures of the pupil and a witness. Indeed, this ritual of record-keeping was captured in the long-running BBC children’s television series Grange Hill, in the 1981 episode which shows Cathy getting the cane (on her open palm) because neither the school nor her mother knew what else to do about her truanting.

A 1985 article in the Guardian reported that official education records, collected shortly before the 1986 ban took effect, revealed an average of 4.7 “beatings” per 100 pupils in English secondary schools each year. In primary schools, the rate was one beating per 100 pupils. These figures were extrapolated at the time by the Advisory Centre for Education to arrive at an estimate of “250,000 officially recorded beatings in each school year in England and Wales - or one every 19 seconds”. So, not exactly infrequent, then…

And how many of these strokes were administered by Coopers canes? Well, if the proportion of the cane market held by Coopers were as high as 70%, which is the figure that applied to John D Dick & Sons in Scotland, then Coopers’ total might have been as high as 7,000,000 acts of violence between 1945 and 1985.3 We’ll never know if that’s correct, but that doesn’t really matter.4 The figure gives us a starting point, something to wrap our minds around as we consider the idea that prestigious companies made money from schools’ callousness. There will also, of course, have been many acts of punishment that were never recorded – blows delivered by plimsole shoes and wooden rulers and blackboard erasers. What we begin to recognise is how threatening school environments would have felt for pupils.

One final reflection: Do we know anything about customers who were particularly fond of Coopers canes? The 1994 Observer article surmised that headmaster Anthony Chevenix-Trench fell into this category. He was headmaster of three elite boarding schools -- Bradfield, Eton and Fettes – between 1955 and 1979. Trench had a reputation for viciously beating boys. Indeed, he was invited to ‘retire early’ from his headship at Eton, in 1969, due to the rumours of his affection for “flagellomania” and alcohol. Two years later, he had been offered a headmaster’s post at Fettes, in Edinburgh, where he died in 1979. The lasting harm he caused to pupils was featured in Alex Renton’s 2023 BBC radio series In Dark Corners, which revealed the extent of sexual abuse in Britain’s boarding schools. It is disconcerting to learn that his colleague Norman Routledge, an award-winning mathematics teacher at Eton, was concerned even in the 1960s with the way “Tony Trench” disciplined pupils. He expressed this view in an interview in 2010:5

“One of [Tony’s] mistakes was that he stopped using the strict and formalised means of administering corporal punishment and [instead] took the boys off to his study, where he could deal with them ‘privately’. I thought he was a very silly man because, needless to say, that was when the tales started going round.”

If that is the view of a fellow teacher, I wonder what Coopers of England would have thought had they realised their products were central to sadistic rituals? How would they have incorporated this knowledge into their legacy?

Perhaps Coopers of England only sold their canes to elite private schools? Perhaps their market never extended into state schools, with their lower social status? Maybe their first foray into the education sector came from King Edward’s School, built in 1867 right next to the village in which the Coopers walking stick factory was based. It was only the expansion of the railway network that allowed the school to relocate to a bucolic rural landscape. It is easy to imagine a casual business enquiry during a gathering of eminent men in the area. If this was the case, then the deal was a lucrative development, given that the schools market was a steady one for Coopers, lasting until the 1998 ban in private schools.

Only a few years after the ban, the Coopers factory itself closed, in the early 2000s. The company signalled their affectionate loyalty to the local community, from which the bulk of their employees had been drawn for more than a century, with the donation of 10,000 chestnut torch-holders. These were intended to be used as part of the annual Chiddingfold Bonfire Night celebrations, held every November. The Torchlight Procession has become a popular draw for tourists and locals alike, with enchanting photographs included in the publicity material lodged on the internet. None of the nostalgic stories told of the Coopers factory mentions the company’s role in Britain’s corporal punishment history.

Perhaps that silence is unsurprising. What was once normalised can later feel shameful. That’s precisely why we need to talk about it.

Bognor Cane Company

A second supplier of punishment canes was the Bognor Cane Company. Established in the early 1970s, the company carried a very different provenance from Coopers. Its reputation was dubious and controversial, and its founder, Eric Huntingdon, was regarded by critics as “eccentric”. It was reported that, by the 1980s, the company was selling 300 - 500 canes per week to schools, all of which were “made for Huntingdon by a pensioner, out of cane about the thickness of a pencil”. Customers could choose from eight different styles, ranging from the 34-inch “senior cane” to the 20-inch “nursery cane”, said to be suitable for young children “generally punished across their parent’s knee”. The canes sold at the price of 50 pence each (plus packing), equivalent to about £2.50 today. Thus, 500 canes would have yielded Huntingdon an income somewhere in the region of £1250 per week, in today’s money. Not a bad living – even if he did have to pay over some of it to his “pensioner” assistant.

Bognor Cane Company came under fire in April 1981 for an advertisement that Huntingdon had placed in the monthly journal published by the National Union of Teachers. The STOPP campaign, intent on impeding corporal punishment, argued that the photographs he had chosen for the advertisement were “lurid” and “salacious” and that they “encouraged sadomasochistic activities”. The campaign group regarded it as “intolerable” that one of the country’s leading teaching magazines should be boosting sales for such an unsavoury firm. Mr Huntingdon’s outraged defence was that “he only sold canes for purely legitimate purposes,” adding that he was a “God-fearing sort of dad”. Stories about the row appeared in a range of mainstream newspapers, including The Times, The Daily Express, The Guardian, The New Standard, and The Sun.

Michael Horsnell, staff writer for The Times, defended Mr Huntingdon’s intentions, arguing there was nothing shocking in the material he had published. Horsnell considered the teenage girls depicted in the photographs as “no more scantily clad [than] the average underground train traveller in summer”. He endorsed Huntingdon’s plan to seek legal advice because he viewed STOPP’s accusations as “utter unmitigated rubbish”. He pointed out that STOPP did not have adequate proposals for dealing with “child crime and violence”, so he was of the view that they should stop expressing derogatory views about those could offer effective means of control.

The tenor of this row, which took place in April 1981, was heightened by the fact that only three months previously, in January, the Inner London Education Authority (ILEA) had taken the decision to ban corporal punishment for all inner London schools, both primary and secondary. It was the fourth education authority in Britain to have taken such a radical decision (following in the footsteps of Brent, Haringey and Waltham Forest). Whilst the Labour-led ILEA was pleased to be taking action against what they branded “uncivilised punishment”, many headteachers were strongly opposed, including members of the National Association of Schoolmasters. It is important to understand that any stories about suppliers of punishment equipment, such as Eric Huntingdon, would have been printed within the context of a highly charged, politicised dispute. Forty years on, we have forgotten just how pugnacious the debate to end corporal punishment became.

By 1987, Bognor Cane Company had been sold to a new owner, Sir Dai Llewellyn. Described as a “socialite Welsh playboy”, Llewellyn would soon become embroiled in a scandal surrounding MP Harvey Proctor, accused of indecent assault against boys. Some of the stories that circulated highlighted Proctor’s association with Ghislaine Maxwell (now imprisoned for her role in grooming under-age girls for the predilections of Jeffrey Epstein). None of this stopped the company from describing itself as “one of the largest manufacturers of punishment canes”, which led filmmaker Michael Moore to interview Llewellyn for his 1994 documentary series TV Nation. In that film footage, we watch Llewellyn gleefully demonstrating the qualities of various canes and defending their use.

“We built an Empire on these. The British Empire was the largest empire that was ever built in the history of mankind. And most of it was achieved with these fine, whoppy canes…. ‘Six of the best’ taught boys not to be naughty, toughened them up, and made them good frontiersmen.”

In 2011, ownership of Bognor Cane Company was transferred to Janus, who describe themselves as “purveyors of erotica to consenting adults”. The ban on corporal punishment in state schools had, by this point, been in place for more than two decades, so it could be argued that tracing the company’s journey to this point is irrelevant. However, the overlap between its ethos in 2011 and the criticisms lodged against it in 1981 is glaring. STOPP always insisted that Bognor Cane Company’s activities were associated with sexualised, sadomasochistic activities, and that has turned out to be true.

One can also detect an overlap creeping in between the ethos of Bognor-Janus and of Coopers. The elite language of ‘purveyor’ has been employed by them both. Coopers was a “purveyor of walking sticks to the gentry,” and Janus a “purveyor of erotica to adults”. Pornography ceases to be quite so sleazy, becoming in fact rather thrilling, once it is wrapped in the patina of class status. Perhaps the same is true for violence against children. Coopers’ reputation for prestige and privilege would undoubtedly have helped to endorse the idea that it was acceptable to hit children, especially when the sticks involved were posh ones. Violence was part of the process of creating gentlemen.

Seedy Mr Brown

One final supplier of punishment canes for which there is documentation is the mysterious Mr K Brown. Operating in the 1970s, he turned out to be “a Canadian-born immigrant…living in lodgings in Leeds”. Mr Brown was, effectively, what we would today call a sole trader, running a small business from his home.

Mr Brown worked with imported Indonesian kooboo rattan, from which he fashioned his merchandise. Kooboo is a highly regarded grade of rattan -- light, durable, dense and flexible, without the tendency to fracture under pressure, as is a risk with poorer grades of rattan and bamboo. He offered customers a choice between two styles of cane, 20 inches for primary pupils and 28 inches for senior pupils, which he was able to supply “at very favourable terms”. By the time Mr Brown came to the attention of the press in October 1977, he had held a contract with Greater London Council for three years, having supplied the Council with approximately 4000 hand-crafted canes during this period. He had outstanding orders for another 1000 canes in the UK and 2000 more in America. If he, liked Bognors, had charged a fee of 50 pence per cane, then that means his income over those three years would have been £2000 pounds, equating to £16,000 today. That must have put a small but noticeable dent in the Council’s budget.

Trouble emerged for the Council only when it emerged that Mr Brown was using an ‘accommodation address’ in Leeds, rather than providing his full mailing address. All his post was delivered through the newsagent ‘R&M Ingram’, who, alongside the sweets and tobacco they sold, offered an accommodation service to a large number of individuals. Why? Because they were all involved in the business of mail-order pornography and sex aids. This discovery was highly embarrassing for the Council. How had they not realised?

The Council explained to the Daily Telegraph that they had been having “great difficulty in securing suppliers for canes”. They had taken the decision to advertise in a London evening newspaper as a means of “inviting tenders for the supply of punishment canes”. Mr Brown had written to say he would be able to supply rattan canes on “very favourable terms”. In fact, his terms were so “low” that the Council considered there was no need for “special inquiries” to be made. Mr Brown was able to supply his canes so cheaply that normal bureaucratic checks could be evaded.

Once the discomforting circumstances came to light, the Council suspended the contract because they “did not really want to appear to be fishing in this particular pond”. While the seedy nature of this transaction may seem astonishing by today’s standards, all one has to do is watch an episode of the 1950s children’s television series ‘Whacko!’ to realise how long sexualised violence has been woven into British childhoods.

When Mr Brown was himself interviewed by a journalist from the Yorkshire Post (in a pub, not in his basement workshop), he volunteered the information that handcrafted punishment canes were but a sideline for him. His primary occupation revolved around “renovating vintage toy models of cars for resale”. The fact that this detail, whether truthful or intended as a diversion, was seen by the reporter as worthy of including in his story illustrates how irrelevant children’s pain was to the story. It was really a scandal about adults and their professional proprieties. It leaves one wondering whether Mr Brown’s profits from toy cars were greater or less than those he earned from devices of brutality.

One final detail of interest that emerges from this incident underlines the haphazard way in which punishment canes were sourced by professional bodies. The Director of Supplies at Greater London Council remarked to journalists that he had no “trade directory” to which he could turn when placing an order for punishment canes. The Council was responsible for “doing their own research into the supply markets”. The Yorkshire Post journalist confirmed that statement by contacting the Department of Education and Science, who oversaw national education policy, and who was quoted as saying that “the choice of supplier for items such as punishment canes was entirely a matter for local education authorities.” In other words, Councils were left entirely to their own devices in meeting their punishment equipment needs. No regulation, no assistance, no guidance was necessary.

Perhaps it is not the level of violence to which children were subjected that is most surprising in this history. Maybe it is the cavalier attitude of the professionals and officials who were overseeing the commission of that violence.

What have we learned?

What have we learned from this sojourn into a sordid corner of Britain’s recent history? Here are two insights I take away.

The first concerns the sparsity of this information. While there are thousands of stories to be found from adults recalling their experiences of being caned at school, it is much harder to locate content from the adults who did the caning. There is even less information to be found about how the system managed procurement of canes from manufacturers. The three suppliers featured in this article are some of the few for whom sufficient details are available.

What sense can we make of those gaps? My reading is that they are a mark of shame. Individuals who once oversaw the infliction of pain on children, and those who sold the implements that made it possible, will find it embarrassing to step forward and say ‘Yep, that was me’.6 That silence is precisely why we should be gathering this material. Caning was not something in which rogue teachers engaged (even though there will have been some who relished it more than others). Caning was a practice woven into the very heart of the educational system in England and Wales. We need to understand how such violence came to be normalised. Documentation is an important part of that sense-making.

The second insight concerns the number of vested interests that were involved in sustaining this practice. Complicity rippled out. It started with the adults most immediately associated, including teachers, headmasters, governmental policymakers, company directors and supportive parents. It then extended to journalists who reported on it without critique, television producers who depicted it humorously, magazines who charged for adverts, taxpayers whose taxes funded purchases, and customers who bought other products from manufacturers. Coopers of England had a wide client base. They would have been aware children were being hit with Coopers’ canes. All of their products carried the same classy logo, with its embedded motto: “Traditionally English”. Customers who purchased any of their products helped to keep the business afloat. This is how collective denial operates. If everyone operates in a manner that implies a practice is acceptable, well…then it is acceptable.

In the USA today, 17 states still legally allow corporal punishment. (This figure applies only to state schools; 46 states permit it in private schools.) Campaigners have not yet succeeded in bringing the controversial practice to a halt. Official records show that in the 2017 school year, beatings with thick wooden boards (which Americans call ‘paddles’) occurred 97,000 times. That could not happen without widespread complicity: school boards to sanction the punishment, principals to write up the policy, teachers to deliver the ‘swats’, lawyers to defend teachers accused of physical abuse, and Amazon to offer paddles for sale at $8.99.

Back in England, the punishment practice attracting controversy today is the use of isolation booths. This practice has grown in popularity in recent years, with some schools arguing that ‘internal exclusion’ is an effective means of dealing with disruptive behaviour, incomplete homework and uniform infringements. Critics argue it that isolation booths constitute emotional abuse, disproportionately affect pupils with special education needs, and contravene children’s rights. In the midst of that debate, a space for commerce has grown up. Office supply companies have begun marketing ‘isolation furniture’, with prices coming in at £175, and schools have begun hiring for the post of ‘Isolation Room Manager’, which carries a salary of £17,000 to £23,000. Advertisements for both of these can now be found in teaching magazines, job recruitment listings and education blogs. No wonder the children’s commissioner in England has described the use of isolation booths as “booming”.

Anything can be normalised. Anything. Fierce Curiosity helps us to see that process more clearly, to notice what we overlook, to question what we tell ourselves is fine.

My sincere thanks go to Colin Farrell, who oversees the World Corporal Punishment Research initiative. This article would have been impossible to write without access to the extensive archive of materials he has compiled, which he makes available to the public at no cost. https://www.corpun.com

The date of 1998 applies only to private schools in England and Wales. In Scotland, a ban in private schools did not come into force until 2000, and in Northern Ireland until 2003.

The logic of my mathematical calculation is as follows:

250,000 beatings per year x 40 years = 10,000,000 beatings

10,000,000 x 70% = 7,000,000 beatings

It is notable that the base figure of 250,000 canings annually derives from 1985, when intense debate was taking place across the United Kingdom about the impending ban of corporal punishment. Many schools had already ceased its use. Therefore, it can be assumed that the use of caning was significantly more frequent in earlier years.

Web of Stories. (2010). Life Stories of Remarkable People. Video archive: @webofstories.

This is one reason I admire Margaret Dick, who is now the director of the family firm J D Dick & Sons. They were the leading producer of belts in Scotland. She does not seek to deny that history, as she makes clear on the company website and in television interviews. See my earlier piece for more: https://suzannezeedyk.substack.com/p/have-we-faced-the-tawse