Why did change for chimney sweeps take so long?

When technological advances couldn't shift societal norms

In 1803, a group of people got together with the aim of stopping a cruelty they saw happening on their streets every day, all over London. They chose a President with high social standing, the Right Reverend Lord Bishop of Winchester, and no fewer than ten Vice-Presidents, all with impressive titles of ‘Esquire’, ‘Earl’ and ‘Marquis’. Before very long, they would even persuade the King to be their Patron. In a short time, they were gaining donations from people across the social spectrum: Lords and clergy and single young women and widows preparing bequests in their wills. And they made sure to give themselves a grand and ambitious title: Society for Superseding the Necessity of Climbing Boys, by Encouraging a New Method of Sweeping Chimneys, and for Improving the Condition of Children and Others Employed by Chimney Sweepers.1

This group of campaigners wanted something straightforward. They wanted children kept out of the chimneys of London.

The city was powered by coal. Burning coal leaves a layer of soot clinging to the inside of brick chimneys, soot which needs to be regularly scraped off or else the chimney itself catches fire, resulting in a risk of the whole building burning down. London was dependent on children preventing such catastrophes.

In fact, it was dependent on young, vulnerable children. London’s chimneys were incredibly small and convoluted. That became apparent when compared to those in, say, France or Germany, which tended to be wider, straighter and often managed by adult trade guilds instead of disparate gangs of children. In London and other cities of industrialised England, chimneys occupied a space of about 14x9 inches. In metric terms, that’s 36x23 centimetres, smaller than a modern fashion magazine, as energy historian Peter Tertzakian points out.2 Chimneys of 9x9 inches were common, and even 7x7 was not unknown. If you were going to ask children to scurry up into such tiny spaces, their bodies would need to be tiny too. That’s why most of the workers employed to do this job were between the ages of 5 and 11 years.

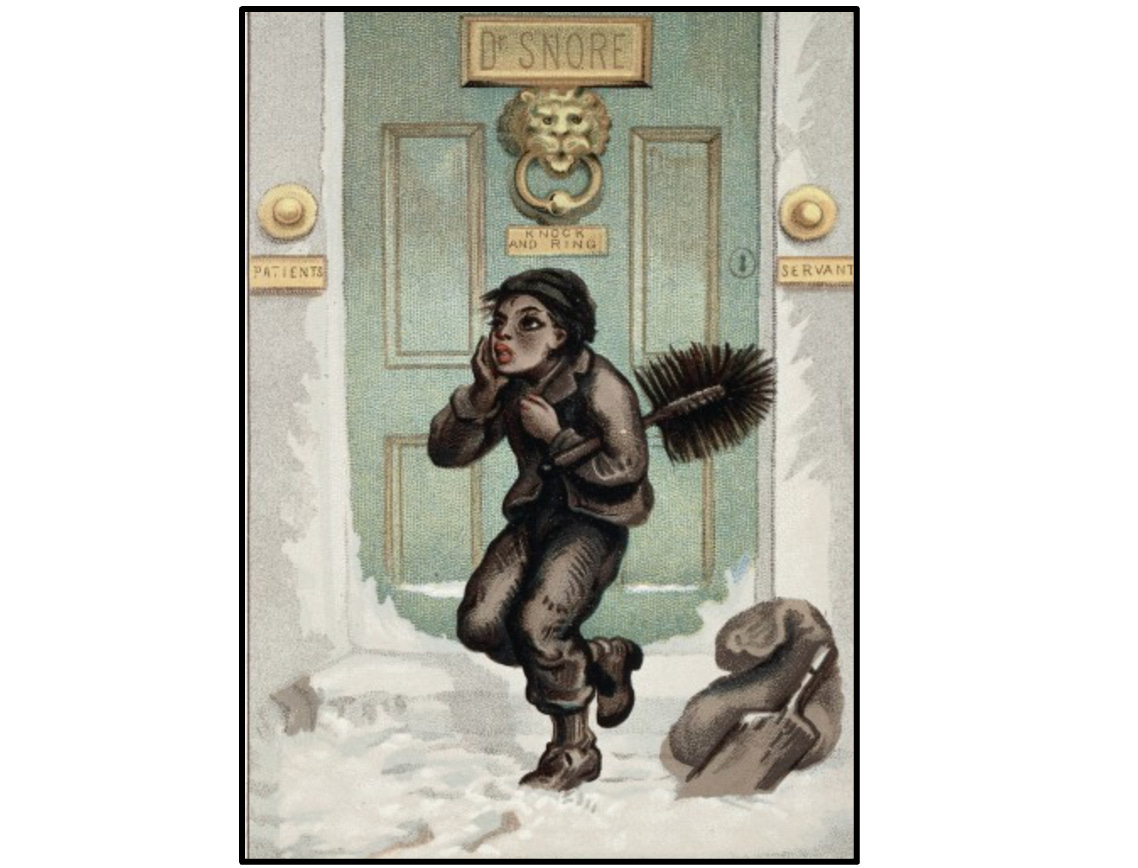

I shouldn’t use the term ‘employed’, though. The children sent into such claustrophobic spaces, wearing climbing caps over their faces to give a bit of protection to their breathing, weren’t paid for their work. They were, rather, apprenticed. Like other forms of child labour, such as the military or mining or factory work, they were regarded as learning a trade from which they might earn a living when they were older. Completion of an apprenticeship in chimney sweeping required approximately seven years. During that time, the children were formally bound to a Master Sweep, dependent on them for food, shelter, welfare and training. By the time they finished their apprenticeship, many would be too crippled or too ill (or too dead) to make much use of the skills they had learned. This wasn’t a problem for the Master Sweeps, of course. They could always buy more pauper children from parishes or desperate families.

Normalised brutality

The lives of these children were gruesome. They were underfed and under-clothed. The single set of clothing with which they were provided did not usually include shoes, and if by chance some kind housemaid supplied a pair, they would be quickly sold off by the Master. The children removed their blackened attire for only two reasons: to bathe two or three times per year or to shimmy naked, ‘in the buff’, up a chimney. It wasn’t helpful if the fabric became ripped, or, worse, if it caught on the rough bricks and left the child unable to move within the narrow space. Preparation for the role included the standard practice of Masters scraping away the thin skin on children’s elbows and knees, with the exposed flesh doused in brine and then held close to a fire in order to create hardened scabs that provided padding against unyielding walls. For warmth at night, the children slept underneath the same bag they would have used earlier in the day to collect the soot they had scraped off, which was then sold on as fertiliser to farmers. They were expected to clear up to 10 chimneys a day, with a quota set for the amount of soot they needed to dislodge and bag every day. Many of the children died in adulthood of ‘chimney sweeps wart’, skin cancer that starts in the scrotum. Others became stuck in the chimney flu, dying of suffocation before anyone could rescue them. Some suffered for days from wounds inflicted by an angry Master’s fists before the relief of death arrived. Very occasionally, some of those Masters were even prosecuted for excessive chastisement.3

Our modern culture has forgotten quite how gruesome the lives of climbing boys were. We can thank Walt Disney for that, because his 1963 award winning film Mary Poppins, with its catchy theme tune, gave us the idea that chimney sweeps tended to be cheery characters. We can also thank the passage of time. It is a relief not to need to think about the blood that flows as skin is scrubbed raw. We don’t have to think about what it is like for a child, swallowing their fear as they look up into a dark winding chimney, to have pins thrust into the soles of their bare feet to get them moving, having paused too long. We don’t need to think much about constant gnawing hunger and piercing cold wind. We don’t have to wonder what state of mind is needed for an adult to decide to take such actions intentionally. If our culture has lost touch with those details, we don’t have to confront any of the distasteful brutality.

It was telling to see that distaste displayed plainly on the face of television personality Joe Lycett when he took part in the show ‘Who Do You Think You Are?’ in 2021. One of his genealogical discoveries was his ancestor Robert Wilkinson, who had served for a time as a child chimney sweep. The episode was filmed in Wimpole Hall in Cambridgeshire, chosen because 10-year-old Robert might well have stepped into the very chimney Joe was standing next to. The stately home had been owned in 1851 by the Earl of Hardwicke, who had voted, as a parliamentarian, against outlawing child chimney sweeps when the 1840 proposal for change reached Westminster. Robert clearly survived to have a family, perhaps because by the next census in 1861 he was serving with the Royal Marines.4

Unlike us, the Society for Superseding the Necessity of Climbing Boys did have to face the brutality. They needed to catalogue its most repulsive details in the hope that these stories would convince an apathetic public to pay attention to the way in which pauper children were treated. The documents left by the Societyoffer a fascinating lesson in the power of denial. Normality can blind us humans to almost anything. Reading through the Society’s reports drives home a sore truth: The business leaders and homeowners of Georgian and Victorian England were dependent on child cruelty in order to maintain their buildings.

Who wants to see one’s self as cruel to children? Certainly not ordinary homeowners, booking for an ordinary cleaning service. Not Master Sweeps, who cast themselves as providing lengthy training in a legitimate trade. Not parliamentarians, who created the laws that oversaw the operation of trades. Not parish leaders, who had located reputable work placements for orphaned children, thereby reducing the pressure on parish funds to feed those children. Certainly not destitute parents, who couldn’t have fed their sons (and sometimes daughters) anyway. Why would any of these adults have been motivated to see themselves as cruel? They were doing what was normal, permitted and necessary.

Fierce Curiosity

There is something stunning in realising that the maintenance of England’s entire building stock relied, for a time, on inflicting cruelty upon traumatised children. It is precisely the kind of uncomfortable insight generated by what I call the lens of ‘Fierce Curiosity’: you see something you wish you hadn’t needed to see.

The discomfort grows as you realise how far the implications extend. It wasn’t just in relation to chimney sweeping that children were exploited. The whole of Britain’s industrial history is incriminated. Indeed, when Professor Jane Humphries’ comprehensive study of the Victorian child labour landscape was published in 2010,5 the Independent newspaper chose a provocative headline for their review of the book: “The industrial revolution was powered by child slaves”.6 Once you begin reflecting, it is easy for a sense of overwhelm to rise as you comprehend the degree to which childhood trauma is woven throughout British history. And if that is a fundamental element of one nation’s history, then it must be part of other nations’ histories too. What are the implications for those societies’ futures, given what is now known about the intergenerational transmission of trauma? Fierce Curiosity leads to a web of questions that are both fascinating and unnerving, if we have the courage to pursue them.

So how and when did the use of children as chimney sweeps change? Were the adults keen to stop the cruelty as soon as they could?

That was certainly the hope of the Society for Superseding the Necessity of Climbing Boys. The most innovative element of their campaign was that they brought something essential: a solution. In an economy fuelled by coal, it was imperative that chimneys be cleaned. If small children weren’t to be utilised in achieving that, how could the task be accomplished? The answer lay in technology. The Society paid carpenter George Smart to design an advanced set of rods and brushes that could dislodge the soot from chimney walls. Within only two years (1805), they held in their hands a perfectly good mechanical device (what they termed a ‘machine’), going by the imposing title ‘scandiscope’. It was effective, transportable and affordable. The Society then paid for the manufacture of a large number of these devices and distributed them free of charge to Master Sweeps, envisioning a future where boys were trained to operate them.

It was possible for the extreme cruelty of child chimney sweeping to be brought to an almost immediate halt. Adults no longer needed to sacrifice children to the coal economy.

A shocking realisation comes in reminders of how stubborn adults can be. The lives of climbing boys saw no radical change. In fact, it would take another 72 years (1875) before the practice of sending children up chimneys finally ceased. Parliament would vote again and again to tweak the law, but they would not vote to preclude the cruelty. Business owners, such as the Bank of England and the East India Company, would host competitions comparing the effectiveness of child-sweeping to machine-sweeping, in order to gain evidence that a change in cleaning policy was of actual value. Inventor Joseph Glass would improve upon George Smart’s original scandiscope design, ensuring technological advances. Newspaper journalists would report again and again on the deaths of children suffocated by soot and ash. Doctors would continue to publish journal articles about the agony and prevalence of scrotal cancer. Poets would pen sentimental poems for magazines: “Ah turn your eyes; ‘twould draw a tear, Knew you my helpless state.”7 Novelists would put chilling words into the mouths of vivid characters, such as Master Sweep Gamfield who remarks gleefully to Oliver Twist that “even if they boys is stuck in the chimney, roasting their feet makes ‘em struggle to extricate themselves.”8 The Society would continue to campaign vigorously, to increase subscriptions, to seek the endorsements of the great and the good, and to publish impressive, heart-wrenching reports. None of it would be enough to bring what was, after 1805, an entirely unnecessary cruelty to a rapid end.

Historian Peter Tertzakian describes in his 2020 story Nobody Tips a Scandiscope what it felt like as he came to terms with this realisation.

“But basic economics wasn’t the primary headwind against the adoption of mechanical cleaning. As I read more about climbing boys, I realized that the persistence of entrenched interests was the greatest source of friction — the slow pace of change wasn’t due to a lack of technology. It was thanks to selfish, human fixations.”9

The final stage in the story of England’s (and Wales’10 and Ireland’s11) stubborn attachment to child chimney sweeps came about not through steady progress, but due to one final tragedy and one final act of campaigning. In early 1875, 12-year-old George Brewster was the latest child to die in a chimney, at Fulbourn Asylum Hospital, near Cambridge. His presence there was technically illegal, as by then the law stated that no child under 21 years of age should be involved in cleaning chimneys, but the law was entirely unregulated and thus routinely ignored. A mere 15 minutes after George had entered the narrow flu as instructed by his Master, William Wyer, he became stuck and began to suffocate under the falling soot. Desperate action was taken, by dismantling the expensive chimney wall so as to free him, but it all came too late. George died within the hour, and William Wyer was convicted of manslaughter.12

This terrible case proved to be unexpectedly helpful, in that the Earl of Shaftesbury read of it in the London newspapers. He redoubled the efforts he had already been pursuing, and by the autumn of 1875 had successfully driven a bill though Parliament that finally outlawed, through stern regulatory enforcement, the use of children as chimney sweeps. It marked the moment dreamed of by campaigners for more than a century.

The value of history

Is it just a history story I have been telling? Or does the lens of Fierce Curiosity lead us to ask what child cruelties exist today that we don’t readily see? Where does our everyday normality blind us, and in what domains does our culture, like the Victorians, prefer a bit of denial? How skilled (or unskilled) are we, having reached the 21st century, at recognising the rationales we fashion for ourselves, the ones that reassure us we are good people?

These are uncomfortable questions. But what is the sense in science acquiring a rich body of knowledge about child development if we do not apply those discoveries to policy and practice? What is the sense in disseminating knowledge if we do not also examine the blocks that exist in our willingness to implement it? Are those blocks due to cultural or psychological or economic or other factors? Is it possible that, in seeking change for children today, we retain the same kinds of “selfish human fixations” that Peter Tertzakian found to be operating during the coal heyday?

Let me reflect on those questions by considering three diverse contemporary challenges.

Extreme poverty. Poverty is once again on the rise in the United Kingdom. Unicef’s most recent Report Card shows that, over the past decade (2012 – 2021), the most dramatic rise in child poverty, out of 39 high-income countries, is to be found in the UK.13 Slovenia, Poland and Latvia rank the best, whilst we rank the worst. The terminology of ‘destitution’ is once again in use, with a 2023 study finding that it applies to over one million children, a rate that has tripled in only five years.14 Some families are coping with the high cost of living through strategies that are dangerous for babies, like watering down infant formula.15 Supermarkets are prevented from discounting formula in the ways that apply to most food items these days, such as in-store promotions associated with loyalty card schemes. Why can’t supermarkets do that?16 Because the UK government restricts retailers from discounting certain products, including tobacco, lottery tickets and, yes, infant formula. Many consumers and critics have been vociferous in their frustration, especially as the restriction derives primarily from the World Health Organisation’s aims to increase breastfeeding rates.17 The Competition and Markets Authority, though, has focused in their own comments on the exploitation being exercised by leading manufacturers of formula, who have raised prices at dramatic rates in order to increase profits, driving ‘greedflation’ during a cost of living crisis.18

Poverty is not inevitable. It is a political choice made by governments, which some corporations find ways to capitalise on. Professor Michael Marmot, highly esteemed for his work on inequality, recently tried to find words expressing his concern for the UK’s children: “It is hard to see this [situation] as anything other than a fundamental, catastrophic failure.”19 That’s essentially what the Earl of Shaftesbury and the Society argued as well, when the word ‘destitution’ was very much part of their own societal vocabulary.

Do the actions of today’s politicians and corporations in fostering extreme poverty constitute ‘child cruelty’? You decide.

Hitting as a disciplinary technique. What about corporal punishment as a means of correcting children’s behaviour? Many people in Britain have come to see this as a moral or human rights issue. But there are still many pockets where it continues to be defended, often on the basis of ‘reasonableness’. While Scotland and Wales have declared parental smacking to be illegal, on the moral grounds that children are entitled to the same protections that adults enjoy, England and Northern Ireland still permit it, as long as parents can show ‘reasonable chastisement’. This is the same defence logic that was available to Master Sweeps, and that kept many of them out of jail, despite their violence.

Other defenders turn to evidence about effectiveness to defend the practice. For example, two UK governmental ministers, the Education20 and Justice21 secretaries, recently defended smacking their own young children, arguing that the evidence from personal experience shows that it “sends a message”. Emily Oster, author of the best-selling 2019 parenting guide Cribsheet, which champions the importance of evidence-based decision making, chose to include a section on spanking in her book. She begins the discussion by acknowledging her “biased” starting position, which is that she would not smack her own children. Such “bias” is not her preferred position from which to evaluate a set of research findings, but she felt it important to include such a “data set” because “at least half” of American parents are believed to use “mild corporal punishment” in correcting children’s misbehaviour. Many American schools still allow it too. Oster believes that her readers deserve the opportunity to evaluate for themselves the evidence on effectiveness of smacking (which she concludes has “not been shown to improve behaviour”).22

Such evidential logic is not far removed that employed by the Society, who attracted clients by through experimental trials of their new machine. Trials that pitted children against technology let business- and home-owners discover for themselves which brought down most soot. The morality of a method was considered secondary to its effectiveness. (If child-sweeping had succeeded in bringing down the greatest amount of soot, would that have been reason enough for clients to continue subjecting children to normal cruelties, instead of switching to a somewhat less ‘effective’ machine?)

And what about gaps as laws are tweaked, piecemeal? When the UK decision came in 1986 to ban corporal punishment for children in state schools, that protection was not automatically extended to children in other ‘categories’. For children in foster care [in England] that had to wait until 1991, in private schools until 1998, and for children in childminding settings until 2003.23 The campaign group Article 39 recently pointed out that these legal protections against violence still do not apply to young people in care who are housed in supported accommodation (eg., bedsits, flats, hostels). The group are concerned because the Children’s Minister in England maintains there is no need for those protections to be extended to this ‘category’ of young person, as it is unlikely to apply to their housing situation.24 Thus, a piecemeal approach results in slower change, with some children remaining exposed to harm. This is the same criticism made by the Society for Superseding the Necessity of Climbing Boys. They argued that piecemeal, incremental, unregulated legislation left pockets of children at risk. They wanted, from the outset in 1803, for chimney sweeping to be banned for all children of all ages and all backgrounds, on humanitarian grounds. They lost the argument because parliamentarians and others disagreed that abrupt and wholesale change was necessary. A gradual pace would suffice.

Does providing adults today with the option or logic of hitting some children as a means of disciplinary control, even if those adults choose not to act on it, constitute a form of ‘child cruelty’? You decide.

Formal schooling. And finally, at what age should children formal education? When are they developmentally ready to sit still, to hold a pencil, to manage emotional stress states, to focus on interpreting abstract symbols of letters and numbers? The global trend has been for formal schooling to start at the age of 6 or 7 years. However, the starting age for all four educational systems in the UK remains at 4 or 5 years. This early age range is now in force in only 12% of countries in the world.25 Although there has been an emphasis on outdoor- and play-based education in recent years within UK education, it has not resulted in a change to the formal developmental structure of any of those four systems.

The efforts that have been most recently impactful in that regard come from the Scottish parent-led campaign ‘Give Them Time’,26 which argues that all parental requests for a ‘deferred start’ of Primary 1 should be automatically granted. That is, children should be allowed and funded to start formal education at the age 5 years instead of 4 years, thereby giving them an extra year in an informal early years setting. After five years of unceasing campaigning (2018 – 2023), the group succeeded in convincing the Scottish Parliament that deferral requests should automatically be granted and funded. It is a celebratory outcome, but it leaves one asking why so much time – five years – was required to convince adults who hold power over children to implement policy change that is fully in line with scientific evidence and global educational trends. Moreover, why, in the final year of the campaign has the group still been uncovering striking differences in the willingness of local authorities to confirm funding and to publicise information on this policy to parents? It has become evident that economic considerations are shaping the degree to which administrators feel able or disposed toward meeting children’s needs. Economics played a similar role in debates about whether the climbing boys system could or should be altered. What were the upfront costs of buying the machines? Who would pay for damages? How much economic upheaval could be sustained while everyone figured out how to better meet those pauper children’s needs?

Does the reluctance of administrators and policymakers to act rapidly in meeting children’s physiological and neurological needs, as science now understands them, count as ‘child cruelty’? You decide.

Adult Responsibility

Maybe, when we look closely, the themes in these contemporary examples don’t look all that different from the ones we saw for chimney sweeps. Poverty and destitution? Physical violence? Evidence-based vs ethics-based policy making? Developmentally inappropriate training (educational) systems? They all seem to be there. Or maybe it feels a step too far to link contemporary challenges with the dreadful ones I’ve described throughout this piece?

It is your option – and responsibility -- as an adult living within your particular community and culture to determine what you think counts as ‘child cruelty’. I am content if, after some Fierce Curiosity, you decide that none of these modern illustrations fit such uncomfortably extreme terminology. There were plenty of Victorians, living within the cosy normality of their own culture and time period, who thought the same about chimney sweeping.

A selection of the Annual Reports from the Society are now easily available to the public, thanks to the work of The Gutenberg Project in digitising archival material. Here, for example, is their 1837 Report: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/67132/67132-h/67132-h.htm

Tertzakian, P. 2020. Nobody Tips a Scandiscope: Discussion Guide. Energyphile Publishing. www.energyphile.org

An extensive account of these practices and the wider history of England’s climbing boys can be found in the excellent PhD thesis written by Niels van Manen. The Climbing Boy Campaigns in Britain, c. 1770-1840: Cultures of reform, languages of health and experiences of childhood. Submitted to University of York in 2010. https://etheses.whiterose.ac.uk/14215/1/534930.pdf

For more on the story of Joe Lycett’s ancestor, see: https://www.whodoyouthinkyouaremagazine.com/tv-series/episodes/joe-lycett-who-do-you-think-you-are

Humphries, J. (2010). Childhood and Child Labour in the British Industrial Revolution. Cambridge University Press. For review, see: https://academic.oup.com/jsh/article-abstract/45/3/856/1746018?redirectedFrom=fulltext

A line from the poem ‘The Chimney Sweepers’ Complaint’ by Mary Alcock, 1799. https://www.invitinghistory.com/2020/03/womens-history-month-chimney-sweeps.html

Charles Dickens’ second novel Oliver Twist was first published in 1837.

Amongst the four countries that comprised the United Kingdom during the nineteenth century, Scotland differed in how it approached the cleaning of chimneys. Whereas England, Wales and Ireland sent children upwards into chimneys, Scottish practice was for adults to pull bundles of rags up and down the chimney from above. This method of chimney cleaning was active even in the 1770s, when early campaigner Jonas Hanway referred to it in his publications aimed at persuading Parliamentary change. https://www.eastcoastsweepservices.co.uk/the-history.html

Kelly, J. (2020) Chimney sweeps, climbing boys and child employment in Ireland, 1775-1875. Irish Economic and Social History, 47(1): 36-58. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0332489320910013

In 2022, an official historic marker was placed on the building where George Brewster died, to commemorate his life and the difference his sad death made for other children who might otherwise have been at risk of becoming a chimney sweep too. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-cambridgeshire-60548227

The supermarket chain Iceland Foods has been brave enough to take an alternative position. They are accepting loyalty points for purchases of infant formula and have reduced their prices by 20%, effectively selling formula at cost price. The Executive Chair, Richard Walker, has stated explicitly that Iceland has done this in the knowledge they are breaking marketing rules. What is their motivation? Walker put it this way in his comments on 1st December 2023: “Some people cannot afford to feed their babies. This is a real issue with real consequences, and we need to do something about it….This is exploitation. We need this to stop immediately.” https://www.theguardian.com/business/2023/dec/01/iceland-boss-hits-out-parent-exploitation-baby-milk-market

Oster, E. (2019) Cribsheet: A data-driven guide to better, more relaxed parenting from birth to preschool. Souvenir Press: Imprint of Profile Books. p 256-258.

This is a point frequently made by Sue Palmer, founder of Upstart Scotland, which campaigns for a kindgarten stage in Scottish education. https://booksfromscotland.com/2016/06/sue-palmer-swedish-schooling-system/

Lots to think about here Suzanne. Fierce curiosity is always easier from a distance…