In 1986, a major change was on the horizon for all four of the United Kingdom’s education systems. Teachers would soon be legally prevented from hitting children. Although it was a restriction that everyone knew was coming, it still caused disquiet and uncertainty for schools.

My choice of the word ‘hitting’ doesn’t seem comprehensive enough to cover the range of experiences to which children were being subjected, but I opted for it because the other words I considered felt too harsh, too pejorative. They risked shutting down curiosity, which would be counterproductive, given the deeply uncomfortable questions that sit at the centre of this piece. We need reservoirs of curiosity to be able to consider them.

How did British society come to see it as normal for adults to respond to children in ways that were intended to cause pain or fear or humiliation? How did we ever think that was a good idea? Why weren’t adults expected to manage their feelings of displeasure in a way that didn’t involve making children feel bad? And how did change for the better finally come about?

Frequent chastisement

If we step back into the years preceding that landmark moment in 1986, we can ask about the triggers for teachers’ displeasure. During the 1960s & 70s, what sorts of things irritated them? Well, children talking out of turn, of course. Columnist Ian Jack1 tells the story of receiving nearly ‘six of the best’ [lashes] for failing to stay silent in his art class. He went home with purple stripes right up his arm, instead of stopping at his wrist. How about failing a spelling test? Miscalculating arithmetical sums? Using your left hand to write? Going to the toilet at the wrong time? Yes, all those could displease teachers enough to have them respond physically. Children’s author Jon Walters2 recalls the “slaughter” that occurred during his first year of secondary school, aged 12, when his ex-military headmaster caned 200 boys for watching a fight outside the school gates because, embarrassingly for the school, the police had to be called to break up the ruckus.

The reality seems to be, judging by the 1800+ responses to Ian Jack’s account of his school days, that almost anything a child might do was at risk of irritating teachers: crying, failing to bring the prescribed number of pencils, blotting the ink in your jotter, smoking, kicking a classmate, forgetting your gym kit, taking too long to change into your gym kit, arriving late, leaving early, failing to keep the queue straight, throwing snowballs from the queue, not eating all your dinner, singing too softly, laughing too loudly. Neither age nor gender was a protection. The 15-year-old boys soon leaving for their first paid job were at risk of sparking annoyance. So were the 5-year-old girls embarking on their first week of primary school. If that seems too sore to believe, one of the disciplinary logbooks covering the 1973 spring term in Edinburgh shows that “494 girls aged between 5 and 11 years were among the 4201 school children belted”.3

Such records were unusual. Headmaster Norman MacLeod, interviewed in 1978 from his Glasgow-based secondary school, said that he did not believe record keeping was necessary because he “believe[d] in the professional expertise of the people in the classroom“. Since he “had faith in the staff in the school”, he was “quite sure punishment was not abused” and therefore no one needed to keep track of it.4

During a 1981 debate in the UK Parliament about corporal punishment, Mr George Foulkes, MP for Ayrshire South (who was in favour of a ban), told the story of how Edinburgh’s unusual 1973 logbooks had come into existence in the first place. A group of leading professional voices in the region had managed to “get an agreement with the teaching unions” that a log should be introduced. He had seen it “as a great step forward at the time”. He recalled their group being “amazed” at what the figures revealed.

“After three terms of logging the acts of corporal punishment, we were amazed that it was taking place on tens of thousands of occasions in schools in Edinburgh. The figures have gone into history. There were children in primary grade 1 who were being belted, 5-years-olds, and children in the sixth year at secondary schools. One would think that there would be no need to use the belt when children were staying on voluntarily.”5

The reality is that we don’t really know how frequently acts of corporal punishment took place in British schools in the 1960s and 1970s. One 1980 study found that only one in 20 Scottish boys made it through secondary school without being belted.6 Television historian Tony McMahon’s recollection is that, in English schools, “far from being used sparingly, it was commonplace.”7 A 1986 Parliamentary debate cited the figure of “200,000 officially recorded instances of corporal punishment each year”.8

We do know, though, which implements were sanctioned to deliver it. In Scotland, the leather belt (or tawse) was standard, generally used to strike the hand. In England, Wales and Northern Ireland, the rattan or bamboo cane was favoured, used especially by headmasters, on either children’s hands or bottoms. Within the classroom, teachers in England were likely to turn to the ‘slipper’, which involved smacking children’s bottoms with the soles of plimsole shoes (similar to trainers today). These are the devices usually envisioned when the 1980s ban on corporal punishment is recalled.

However, when you listen to the stories from those who were students in the 1960s and 1970s, it becomes apparent that the ‘teacher’s toolbox’ contained a very wide array of implements that were used in delivering ‘punishment’. Children had wooden-backed chalkboard dusters thrown at them. They were hit over the head with books. Their knuckles were rapped with metal-edged rulers. Stories of being slapped and punched by teachers are not uncommon. The deluge of responses to Ian Jack’s 2018 article reveals a shocking catalogue of violence and aggression: shoes thrown at pupils’ heads, fag ends (cigarettes) flicked onto their laps, rosary beads swung against the back of heads, hair yanked to pull children into the air, bare legs smacked with hands or rulers, chanters rapped across knuckles during piping class, fingers dug into the tender flesh of elbows, ears twisted, lumps of wood from carpentry class thrown at heads, tools from carpentry class thrown at knees, the long pole for opening windows brought down on shoulders. The list seems interminable. It strengthens my sense that, while the term ‘hitting’ may feel safe for us adults to use while we contemplate the past, it is a paltry descriptor for what children actually experienced.

For so many children, this was just normal daily life. That wasn’t the case for all children, of course. In the late 1970s, for example, Portobello High School, in Edinburgh, obtained the agreement of all their teaching staff to end corporal punishment.9 At the other end of the spectrum, the Headmaster of Plockton High School was “severely censured” in 1979 by the Highland Education Committee when his disciplinary methods became too “extreme”.10 It is clear, though, that the threat of violence was prevalent enough for it to be viewed, as one of the respondents to Ian Jack’s article put it, as “just part and parcel of being a schoolboy”.

Fierce Curiosity

How could such violence have been ‘normal’ anywhere? How had it become acceptable, tolerated, commonplace? What motivated teachers to behave in this way? How unsupported or angry or entitled did they need to feel? What long-term consequences for children resulted from navigating such a hostile environment on a daily basis?

These are questions that occupy the territory I call Fierce Curiosity. They are the uncomfortable, distasteful questions, the ones you wish you didn’t have to ask. Ordinary levels of curiosity won’t do for these kinds of reflections. You need deliberation with an edge, an intensity. Fierce Curiosity matters because, unless we have the courage to face uncomfortable questions, we risk doing unintentional harm to children. Even with the extremity of the actions I have recounted above, I don’t imagine most of the teachers thought of themselves as doing ‘harm’. It is more likely they saw themselves as ‘keeping up standards’.11

That’s why stories of the past are valuable. They enable us to see what the inhabitants of another time often could not, blinded as they were by their normality. The lessons we learn from their myopia can help us in seeing beyond our normality. Recognising their denial can help us avoid our own.

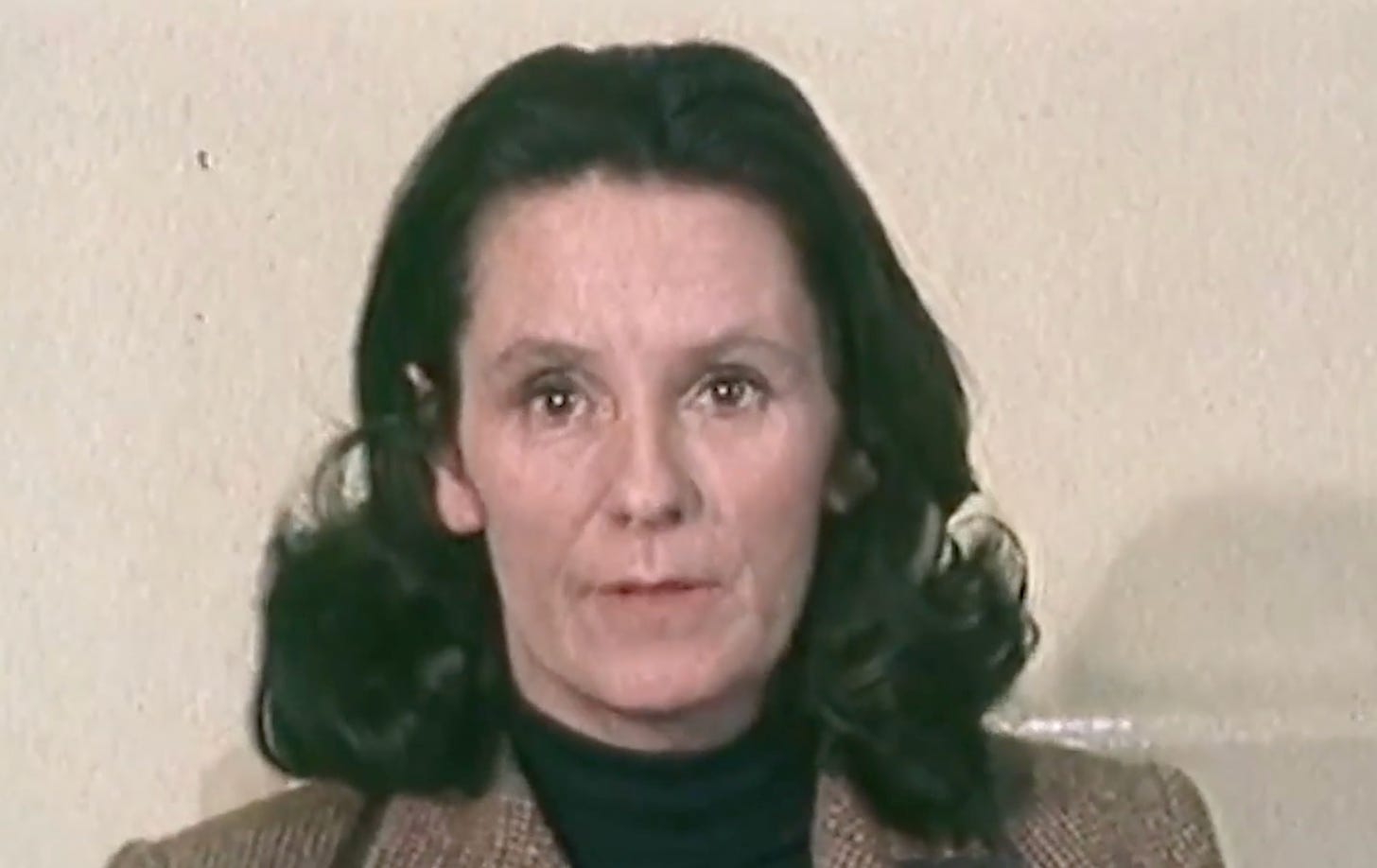

In 1982, two determined Scottish mothers, Grace Campbell and Jane Cosans, won the case they had brought to the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR). Their goal had been a simple one: to protect their sons from being hit by teachers at school. When the schools objected, saying that they had a right to exercise corporal punishment where they saw fit, the two women took their arguments to the judicial system. They endured dislike from the teaching profession and from their communities, but their dogged determination eventually yielded a magnificent change for children’s lives. The Court affirmed that teachers did not have an automatic right, in their role of in loco parentis, to inflict violence on children’s bodies. In the years that followed, each education system (England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland) had to decide to how respond. By the end of 1987, corporal punishment was no longer deemed acceptable in any state schools.

From the vantage point of today, 40 years on, it can seem that the decision must have grown out of the pace of natural progress. One might think: ‘Surely most people had already come to realise that hitting children wasn’t okay?’ The answer is no. Some had, but ‘most’ hadn’t. Fierce Curiosity lets us appreciate that there was no ‘surely’ to this societal change. The courage and vision needed by these two women, and the many other campaigners also working for this change, was immense. Neighbours quit speaking to them. They had bricks thrown through their window. Phones were bugged. The video produced by the Council of Europe in 2015 conveys something of the tenacity they needed for unexpected leadership in making this societal change.

The logic for change

One of the aspects of this case that surprises people is the logic of the ECHR’s decision. It was not, at its core, grounded in a child’s right to be treated with respect and dignity. Although the Court would certainly support that view, it wasn’t the logic in this case. The 1982 decision in Campbell and Cosans vs UK was actually grounded in parental rights. The court proclaimed that parents had a right to ensure their children were educated in line with their own philosophical convictions. If they did not wish their children to be belted, caned or slippered, then schools could not take such action.12

This was a judgment that caused consternation within the education system. That sense is clearly reflected in the response of the National Association of Head Teachers (NAHT) in February 1982.

“This decision will cause confusion in schools. They will have to distinguish between children who are allowed [by their parents] to be beaten and those who are not. You cannot have one section of pupils who may be subject to punishment and another section who cannot be punished.”13

The advice from David Hart, General Secretary for the NAHT, was that “members should carry on caning.” (Wow, what words of their time! “Allowed to be beaten.” “Subject to punishment.” “Carry on caning.”)

Eventually, the unions and other bodies resolved the complicated problem of “inequalities between students” by making corporal punishment illegal for all students. Civil servants could stop worrying about whether the default should be for parents to opt-in or opt-out of allowing their children to be beaten. The solution was that all corporal punishment would cease for all students.

Interestingly, some regions in America today find themselves facing a similar “inequality amongst students”, but they have not followed in the footsteps of Britain’s solution. Instead, they have chosen to embark on the administrative and moral nightmare of having parents make the opt-in or opt-out choice. Parents decide whether they wish to give or withhold permission for their child to be beaten by school officials.14 In the 16 states where corporal punishment is still legal in America, the implement usually chosen to inflict it is a rectangular wooden plank called a ‘paddle’. You can order them from Amazon for less than £10. Typically, the plank is about 4 inches wide and up to half an inch thick, with holes drilled into it. These are designed to reduce air resistance against the surface of the paddle, allowing it to travel more swiftly as it swings toward a child’s bottom.

Returning to the ECHR’s decision in 1982, cultural historian Andrew Burchell has remarked on the significance of its logic in giving priority to parental authority.

“The verdict is significant because it negated both the child’s right not to be hit and the teacher’s right to employ force against any child. Parents’ own disciplinary authority was validated as the primary source of punishment.”15

Technically then, this was a case about parental rights rather than about children’s human rights – even though children’s rights were certainly served. Having said that, it was not all children whose rights were ensured. Those who attended private schools throughout the UK, whether as boarding or day pupils, would have to wait until 2003 before they were equally protected from corporal punishment.16

It is ironic that, over time, our culture has tended to forget this legal framing. Perhaps that is due to relief at the outcome: children are protected from violence. Perhaps it is because the discourse of human rights has become embedded in our 21st century reasoning. Perhaps it is that we have had a chance to witness human rights legislation in action, as occurred when the Scottish Parliament voted to change the law in 2019 so that parents too are now prohibited from physically chastising children. Perhaps it is that we can no longer quite conceive of classrooms as places where any child would have to “run a gauntlet of abuse from adults” (to quote another of Jack’s respondents).

Whatever the reason, it is undeniable that this case has had a dramatic cultural impact. We have radically altered our views about what children deserve. Andrew Campbell, son of Grace Campbell, is still celebrating that change. “Thirty years on, if you ask anyone under the age of 40 whether they think corporal punishment is a sensible thing, they will say ‘What??’. I am impossibly proud of my parents for that.”17

The value of pragmatism

Why do I find this case so valuable, from the perspective of Fierce Curiosity? It isn’t predominantly because of the improvements it yielded for children’s lives, delighted as I am by that outcome. Rather, I value it because it serves as a stark reminder that whatever I may find to be shocking or brutal or unacceptable is not necessarily seen that way by others.

The violence I itemised earlier was so normalised in the 20th century that, when challenged, many schools and unions defended it. Let me reiterate that this was not true everywhere. The STOPP campaign (Society of Teachers Opposed to Physical Punishment)18 had been founded in 1968. Politicians such as George Foulkes were successfully negotiating with teaching unions for change. Many teachers had reached a personal position that they did not find corporal punishment to be morally defensible or practically effective. But as this societal debate came to a raging head in the 1980s, many other teachers and schools still did not see the problem. They believed they had a right, even a duty, as adults in a professional role, to respond to children in this way. Grace Campbell and Jane Cosans were not able, at that point in British history, to bring a case to court that simply argued: “We think children deserve better. Don’t you too?” Instead, they and their legal teams had to find a way of framing their argument so that it had the best likelihood of yielding change within their particular time period. In short, they had to be pragmatic.

This may sound an obvious statement: ‘If you want change, you need to be pragmatic.’ However, pragmatism can feel limiting and frustrating when you know the urgency of meeting children’s developmental needs. It is easy to become overwhelmed by a sense of outrage or worry or impatience. Exhaustion is always a risk when dealing with confusion about why another person cannot see the harm you do or why they resist acting on evidence that holds solutions.

What Grace Campbell and Jane Cosans teach us is the value of pragmatism. When I’m caught in cycles of mounting despair or frustrated overwhelm, I turn to their memory. They remind me that what I’m looking for is a way to frame the case I want to make. With that re-orientation, I can start looking for new words that might help others to see differently.

Jack, Ian (2018) I was belted at school. The Guardian. 24 March. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/mar/24/belted-school-education-corporal-punishment

Walter, Jon (2016) Why I’m glad corporal punishment is now only found in books. The Guardian. 1 July. https://www.theguardian.com/childrens-books-site/2016/jul/01/corporal-punishment-jon-walter

See Ian Jack’s 2018 piece. [Footnote 1]

David Jessel on corporal punishment (1978) Video V1180a lodged on Corporal Punishment website. www.corpun.com

Hansard Records (1981) UK Parliamentary Debate on Corporal Punishment. 8 June. Contribution of Mr G Foulkes, beginning at Section 135. https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1981/jun/08/corporal-punishment

Craig, Carol (2018) Scotland the cruel: The legacy of our sadistic past. Scottish Review, 21 March. https://www.scottishreview.net/CarolCraig420a.html

McMahon, Tony (2023) Corporal punishment in 1970s schools. Blog: Three decades of history with TV historian Tony McMahon. September. https://the70s80s90s.com/2023/09/02/corporal-punishment-in-1970s-schools

Hansard Records (1986) UK Parliamentary Debate on the Abolition of Corporal Punishment. 22 July. Section 231. https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1986/jul/22/abolition-of-corporal-punishment

Hansard Records (1981) UK Parliamentary Debate on Corporal Punishment. 8 June. Contribution of , beginning at Section 135. https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1981/jun/08/corporal-punishment.

Farrell, Colin (2007) The cane and the tawse in Scottish schools. www.corpun.com

It is notable, though, how many of Ian Jack’s respondents describe one or more of their teachers as a “sadist” who enjoyed inflicting pain on students. Carol Craig also uses the term ‘sadistic’ in the title of her 2018 piece. [Footnote 6]

End Corporal Punishment (2018) Summary of decisions relating to the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms. https://endcorporalpunishment.org/human-rights-law/regional-human-rights-instruments/european-convention-for-the-protection-of-human-rights-and-fundamental-freedoms/

BBC website. On this Day, 25 February 1982. Parents can stop beatings. http://news.bbc.co.uk/onthisday/hi/dates/stories/february/25/newsid_2516000/2516621.stm

Dahl, Richard (2022) Is corporal punishment legal in US schools? Find Law website. https://www.findlaw.com/legalblogs/law-and-life/is-corporal-punishment-legal-in-schools/

Burchell, Andrew (2018) In loco parentis, corporal punishment and the moral economy of discipline in English schools, 1945 – 1986. Cultural and Social History, 15(4): 551-570. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6285843/

The decision to outlaw corporal punishment in private schools was taken at varying times across the four jurisdictions of the UK. In England and Wales, the date was 1998; in Scotland, 2000; and in Northern Ireland, 2003.

Council of Europe (2015) Corporal punishment at school. How two parents decided to change things. https://www. youtube.com/watch?v=ZOre9b5rNas

Harris, Ray (2021) Ending corporal punishment. https://rayharris57.wordpress.com/2021/11/23/ending-corporal-punishment-2/