What strategies helped end corporal punishment in Britain?

When a canny educational leader brought caning to a quiet conclusion

My Fierce Curiosity series is filled with questions about denial and stories of change.

What domains of pain have adults introduced into children’s lives? How and when and why did change finally come about? How aghast or angry or relieved should we be feeling in the present at these stories of the past? And what are the domains of pain that we adults might be overseeing today, but which we haven’t really noticed because we’re getting on with our ordinary, everyday, well-intentioned lives? What guilt or shame or overwhelm do we risk feeling if we choose to look closer and step out of the comfort of denial?

These are the sorts of edgy questions I like exploring in this series. I welcome the stories that come along to help me answer them.

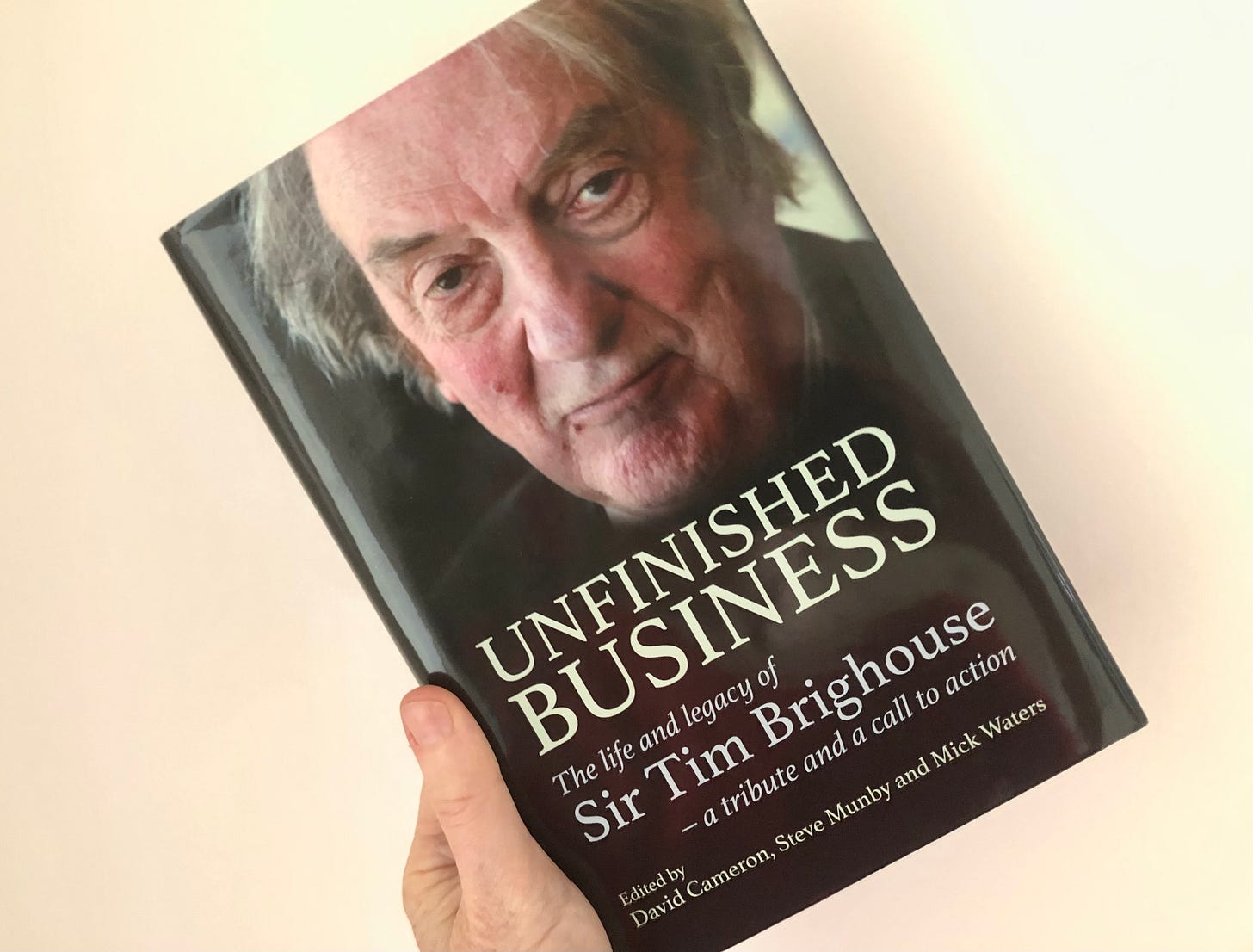

And the story in this piece did, indeed, just ‘come along’. It turned up in the new book celebrating the life and legacy of educational visionary Sir Tim Brighouse, who sadly died in December 2023. A group of his colleagues, as an act of hope, affection and mourning, got together to write a book about his impact and his wisdom. They wanted it to be more than a tribute, though. They wanted it to be a call to action, highlighting the unfinished business Tim had left behind and the ways we could all be part of carrying forward his vision of a more humane world.

That’s the name of the book: Unfinished Business. And that’s its subtitle: A Tribute and a Call to Action.1

A book of stories

The book contains a striking 64 chapters, with contributors ranging from teachers to students to politicians to policymakers to critics to journalists to fangirls who only ever met him once.

And there’s a chapter from his son, Harry Brighouse.

It is Harry’s chapter from which I have taken the following story. He recalls how Tim’s canny, pragmatic, unassuming management style instituted a ground-breaking cultural shift. Tim brought the caning of children to an end, in a Conservative-led educational authority. He did so without directly challenging anyone or shaming anyone or even bossing anyone about. He managed that shift even before the law compelled it.

Here is Harry’s story of his father — three short paragraphs extracted from 64 chapters of stories of change.2

“Tim was a fierce opponent of corporal punishment. Becoming Chief Education Officer in a Conservative-led local authority (Oxfordshire in 1978), he realised it was pointless having an argument about whether it was okay to beat children, and he knew that unilaterally ending it was beyond his remit. As he put it, “In a time of cuts, if I’d gone to the politicians and asked them for money for canes, they’d have asked me how many I wanted and did I want the luxury versions.” But when, in the mid-1980s, councillors began panicking that it might be impossible to comply with the then inevitable law against corporal punishment in schools, Tim assured them that they needed to do precisely nothing because he knew that none of the schools [in Oxfordshire] practised it.

He had initiated an annual survey on how often schools caned pupils. When the results were in, he gave each school the full list, showing the numbers of canings at each school, but with the names of all schools [other than their own] redacted. The head at the top of the list was shocked to see that his school administered 25% of all the canings in the local education authority (LEA), but Tim said something to the effect of, “It’s okay. That’s the way you like to do things at your school. I often hear the swish as I drive by.” (I realise he might have made that bit up, although many readers will know it is believable of Tim.) The following year canings were down substantially, even at that school, which was still, though, at the top of the list, now accounting for 33% of all canings. Again, Tim was reassuring. Within two years, the league table was empty. There were no canings.

In political philosophy, we distinguish between ideal theory and non-ideal theory. Crudely, ideal theory is about what a just society would be like; non-ideal theory takes those values and asks how they tell us to act in our unjust society, which we might be able to improve but cannot expect to make just by our actions. You cannot do non-ideal theory without ideals; but you also cannot do it without a clear vision of where you are and without acknowledging the unwelcome constraints you face. Tim was principled, yes, but also pragmatic and, in the best sense of the word, opportunistic.”

Stories of leadership

I have written in other pieces in this series about individuals who helped bring the beating of children in Britain’s schools to an end, in the mid-1980s. It is the stories of the official STOPP campaign and the two Scottish mums who brought a legal case to the European Court of Human Rights that are most often recalled. Those are important stories of change. They should be told. Many people have not heard those stories. Most modern headteachers have never had cause to wonder what it would feel like to know that their legacy would include entries they had made, in their own handwriting, in the school’s Punishment Record.

Part of the power of this story of Tim Brighouse is that it got recorded nowhere — until now. We wouldn’t know anything about it at all if his son had not chosen to write it down. It is an extraordinary story of quiet, practical change, led by one man who had ideas about how he could make the world more just for the children in his care. It is story that reminds all of us that we could do that too, if we wanted.

It is a story that illustrates why the three colleagues who (still) love him — David Cameron, Steve Munby and Mick Waters — settled, as they jointly edited this book over the past year of grieving, on a pithy phrase that reminds the rest of us how we might approach the endeavour of making change in our own worlds. That phrase is: Be more Tim.

You can buy the book from the publisher on this link. Proceeds are being donated to charity. Tim would also have added (if he had found a way to tolerate such emotive fuss being made about him) that you can order it through any small, independent bookshop near you.

Unfinished Business: The Life and Legacy of Sir Tim Brighouse – a tribute and a call to action. Edited by David Cameron, Steve Munby and Mick Waters. Published by Crown House Publishing. 2024.

Chapter 1: Finding the Holy Grail. By Harry Brighouse. Pgs 6 – 7.

Wonderful thoughtful piece Suzanne - thanks for sharing - very inspiring!

An excellent read Dr Zeedyk, Tim sounds like he was a good egg. I am delighted to see your writing again.